Lecture 2

Urban Data

Maps + Census

Network Science Institute | Northeastern University

NETS 7983 Computational Urban Science

2025-03-31

Welcome!

This week: Introduction to Urban Data - Census data as a tool for understanding urban systems

Aims

- Understand the uses of census data in Computational Urban Science

- Understand how data from the census can complement large-scale behavioral data

- Understand the strengths and limitations of census data

- Understand special considerations when combining census data with individual-level behavioral data (i.e. Ecological Fallacy and the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem)

Practical

- Conduct an analysis of residential accessibility to transit stations in Boston.

- Explore cross-correlation of census variables.

- Conduct a Social Area Analysis to identify key social factors differentiating areas in the census.

What is the census

A comprehensive survey measuring population characteristics

Aim: count all individuals in a country / region (and some of their characteristics)

Around the world:

In most countries, censuses occur every 10 years

Some countries rely on very old censuses (DRC - 1984, Iraq - 1987, Afghanistan - 1979)

Different variables are collected by different countries. For example, censuses of race and ethnic origin are banned in France

Censuses are expensive! The 2020 US Census cost $13.7 Billion

The US Census

A population census is required by the constitution every 10 years

The census determines electoral representation and re-districting, as well as billions of dollars in federal and state funding

The US Census (formerly called the “short form” census) collects basic information:

Number of people living in a household

Basic demographics: age, sex, race, hispanic origin, relationship to householder

Housing tenure (whether a family owns or rents their home)

American Community Survey

Annual survey measuring detailed population characteristics in 4 domains: Demographic, Economic, Housing, Social.

See the ACS Subjects Explorer

Detailed survey of a sample of US households (3.5 Million in 2015).

- The ACS has replaced the “long form” census.

ACS responses are: re-weighted to adjust for sampling bias, modeled to impute responses for small areas.

Sufficient data is required for accurate modeling of detailed population characteristics

- ACS estimates are released in rolling 5-year windows (i.e. 2020 release uses data from 2016 to 2020).

The Census is a form of “big data”

Although we now consider the Census to be “traditional data” - comprehensive data on population characteristics were a huge advance in quantitative social science.

For example, the First UK census was the basis for E. G. Ravenstein’s “Laws of Migration”

Census data was tabulated by hand and revealed regularities in migration behavior.

These regularities supported the Gravity and Intervening Opportunities models of human mobility (which we will use later in this course).

Fast vs. Slow data in CUS

Traditional urban studies research is heavily reliant on Census data

Ideas like residential anchoring, proximity-based accessibility produce scientific questions which are tractable using census data alone.

“Fast” behavioral data has expanded the questions that we can ask about urban systems.

What differentiates “fast” big data from traditional big data like the census?

- Volume: “data that outstrip our capabilities to analyze” [1]

- Velocity: continuously updating databases permitting longitudinal and near real-time analyses

- Variety: broad range of possible formats (structured and unstructured)

Combining census and behavioral data

Census data only represent some aspects of human behavior. Luckily, behavioral data often complement (rather than duplicate) information from the census.

Variables such as education, race, gender, and income, independently explain approximately 50–55% of the variation in economic outcomes (e.g., median household income or property values) [2]

Similarly, exposure between socio-economic status (SES) groups driven by demographic characteristics accounts for half of the variance in cross-class friendships [3]

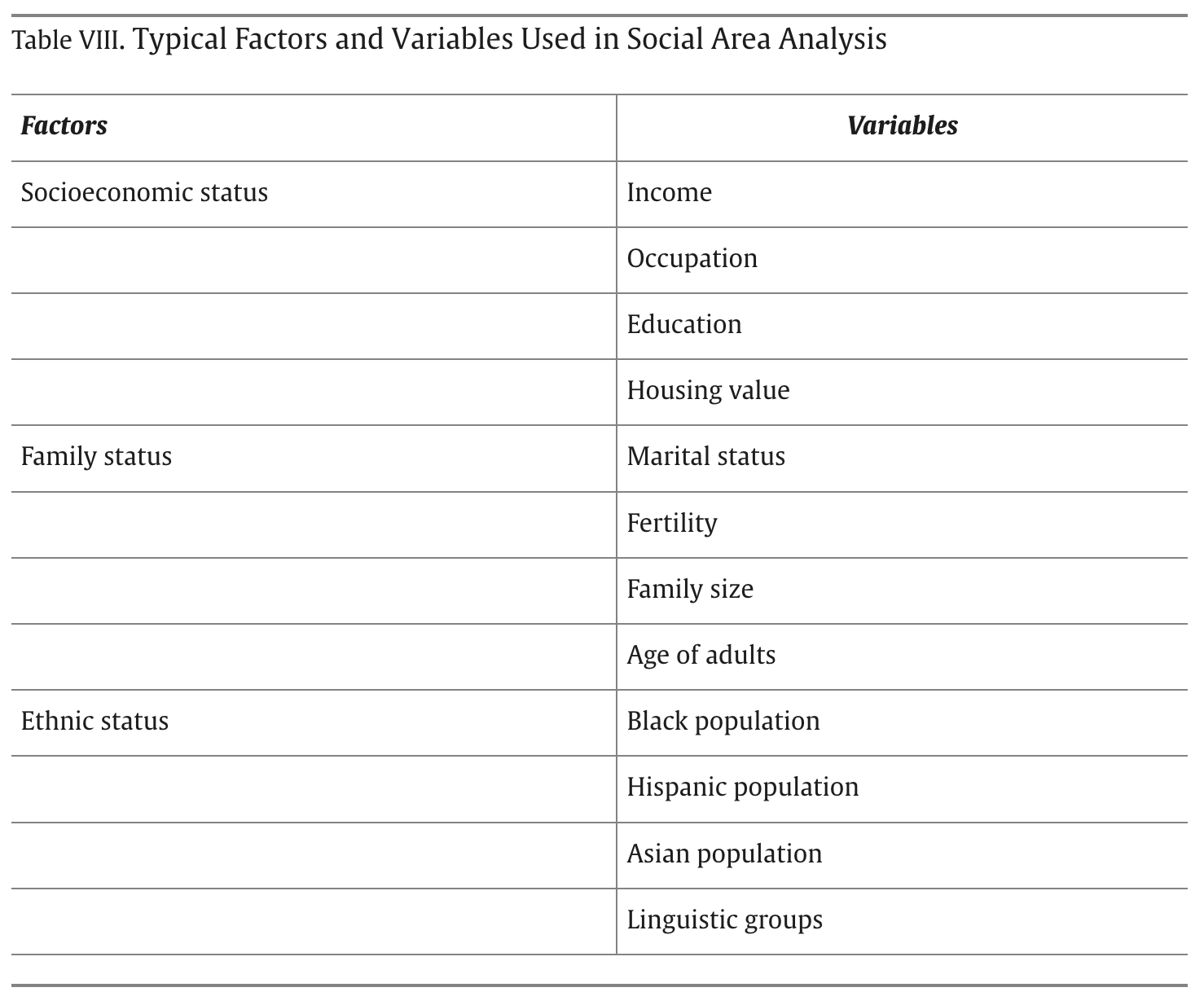

Today’s practical: Social Area Analysis

Consider the underlying social “factors” which are captured by the census.

Can a large number of census variables can be reduced to a small number of “factors”?

In the US, repeated studies have shown 3 important factors: socioeconomic status, family status, ethnic status [4].

What aspects of human behavior in cities are not captured by these factors?

*

Limitations of census data

The census is a “gold standard” survey, but it still has limitations:

- Systematically difficult groups (young men, people with irregular addresses, undocumented people)

- Small population subsets even with the large sample of the ACS, it is hard to capture low-frequency population groups

Census authorities spend a huge amount of effort designing their sampling strategy and correcting systematic bias. These issues are general to all data collection, and play an even greater role in large-scale behavioral data.

Units of analysis

Take note of the unit of analysis that a census variable refers to!

- This is particularly important when comparing variables to one another or normalizing / standardizing variables

Census variables can refer to:

- Individuals 👥 (Age, Gender, Race/Ethnicity, Educational Attainment, Employment Status)

- Households 🏠 (Income, Household Size, Housing Tenure)

Different variables refer to different population demonimators!

The percentage of employed people in meaningful as a proportion of the working-age population

Proportion of the population below a poverty threshold is usually measured for households, not individuals

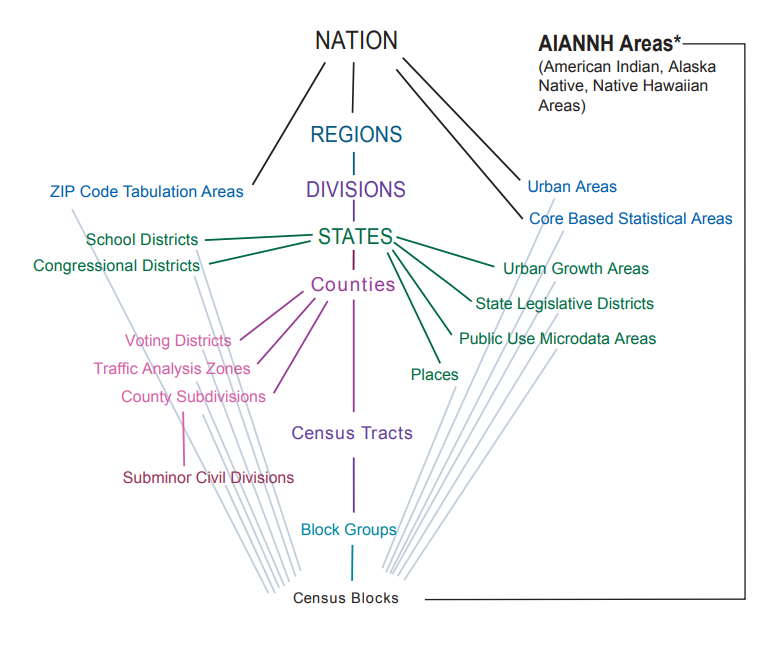

Geographic references

Familiarize yourself with the hierarchy of US Census statistical geographies

- Geographies listed in the central “trunk” of the plot nest within one another.

Hierarchy of US Census Statistical Geographies

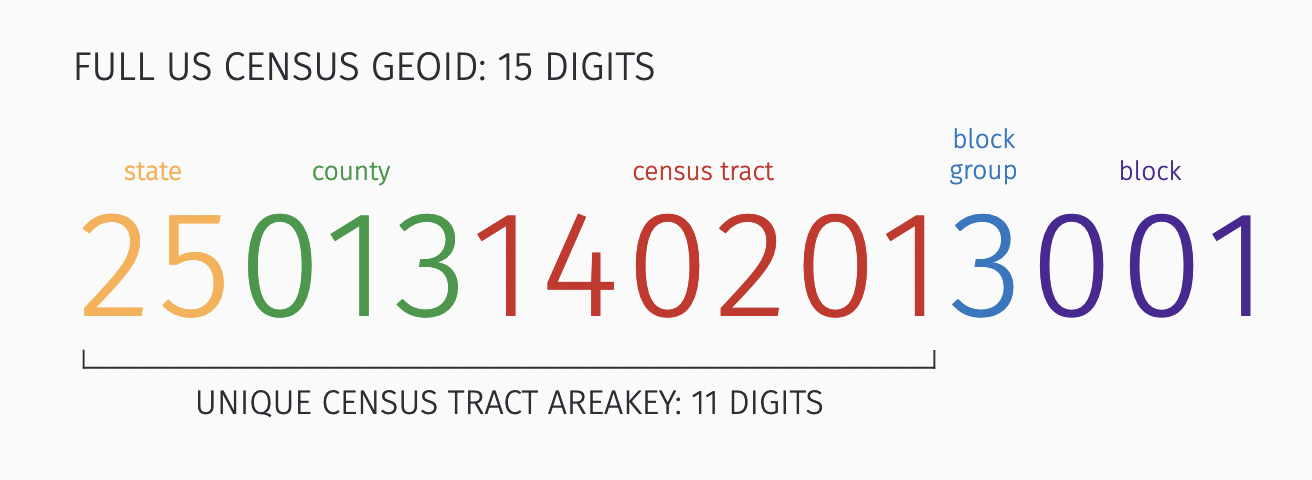

Geographic identifiers

Every geography used by the census has a unique identifier called a GEOID.

For nesting geographies, you can move up and down in the geographic hierarchy by adding / removing characters from the GEOID

- This is very helpful as it speeds up the process of spatial aggregation, converting a spatial operation to a simple string manipulation

Warning: take note of boundary changes. GEOIDs are re-defined every 10 years, meaning that additional work is required to compare data between decennial censuses.

Combining census data with behavioral data

Many large-scale behavioral datasets are missing demographic information, which can be attributed to individuals based on their residence location. This raises the ecological fallacy: the problem of making assumptions about individuals based on group characteristics

- Which demographic characteristics can be attributed based on residence? Which cannot? Why does this approach work for some characteristics better than others?

Ecological fallacy & MAUP

The problem of Ecological Fallacy is connected to the general Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP)

Consider: How accurate is assignment of income by residence at the Census Block Group level? What if we instead use ZIP Codes?

A classic example of MAUP: you can change the results of a regression analysis simply by re-districting your data, without changing the underlying distribution of individual variables.

A helpful concept: in Geostatistics a spatial support is the fundamental unit of a geostatistical analysis

- For example, in satellite imagery data a support would be a set of pixels with specific dimensions. In census data, it is the chosen spatial tesselation.

Always consider the role played by your choice of geographic units. There is no “answer” to the MAUP - you need to use your own scientific judgement to choose the appropriate spatial scale for your analysis!

Sidenote: Privacy and the census

Individual level census data poses severe privacy risks. What if you knew the household income of everyone in your neighborhood?

The US census has recently changed to a privacy model that uses differential privacy (calibrated random noise) to protect privacy.

There is an active debate about the adoption of differential privacy: does the noise required to achieve privacy result in low data utility?

- An interesting case study: how much money is mis-allocated from federal and state budgets because of random noise introduced in census statistics?

See the infographic: A History of Census Privacy Protections

References

CUS 2025, ©SUNLab group socialurban.net/CUS